The founder of the Twinkie Diet, a professor of nutrition at Kansas State University, lost 27 pounds (12 kg) in two months on a diet of ultraprocessed sweets. He even improved his health marker scorecard: his “bad” (LDL) cholesterol, “good” (HDL) and triglycerides all moved in the right direction.

His secret? Quantity over quality. He limited himself to only 1800 calories worth of Twinkies, rather than his usual 2600 calorie diet.

This article uses the Twinkie Diet, and the latest science, to answer the age old question: Which diet is best for weight loss?

Note: This article focuses on the goal of weight loss, and separates this from the pursuit of long term health. I’ve made the assumption that the optimal strategy for weight loss may not necessarily be the same as the optimal strategy for long term health.

Weight Loss Principle Number One

While I wouldn’t recommend the Twinkie diet, I am not surprised that it worked (at least once). Despite all the hype, how much you eat is a much stronger weight loss driver than when you eat, or what you eat.

I call this critical first principle of weight loss: calories are king and queen (CAKAQ).

Compelling scientific evidence for CAKAQ comes from “isocaloric” human trials — studies in which subjects consume one of two different diets with the same calorie content. These trials fail to show consistent, meaningful differences in weight loss based on dietary composition (e.g.low fat vs very low carb; high protein vs high carb). It’s the same story with real-world trials comparing low and high levels of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

A closer look at studies of fasting for weight loss further reinforces the importance of calorie balance. We don’t tend to see difference in weight loss between continuous calorie restriction (e.g. cut 25% per day) and equivalent intermittent fasting (e.g cut by 100% every fourth day), as reviewed here and here.

There is no magic diet. To lose weight, we must shift the energy equation. Exercise aside, you won’t lose weight unless you cut calories.

Weight Loss Tip: The other side of CAKAQ is that you can gain weight on any diet, regardless of how healthy your choices are. For those on a tight calorie budget, it can be helpful to set out a portion of calorie dense snacks (like nuts or hummus) before digging in, rather than munching endlessly.

Indeed, most reviews of weight loss reach the same conclusion — the bottom line comes down to calories in versus calories out.

At the same time, I don’t actually believe that all diets, and all calories, are equal, nor do I recommend the Twinkie Diet as an optimal choice.

Are All Calories Equal?

Aside from taste and pleasure, diets differ dramatically in their nutritional upsides and downsides which, in turn, impact our physiological, mental, and emotional responses. This list scratches the surface of why our choices of what, and when, to eat also matter. Stay tuned for gory details in my upcoming article!

- Quality of weight loss. While most diets result in similar fat loss, the amount of water and muscle lost is more variable.

Weight Loss Tip: Keep an eye on protein during weight loss to help mitigate loss of lean tissue. When cutting calories, our total protein needs don’t change, but the percent of calories required to get the job goes up. In my case, I need 11% of calories from protein to cover my basic needs at 1800 calories but 17% if I cut down to 1200 calories. Whether or not there is an meaningful advantage of going beyond our basic needs is unclear. Learn more here about protein needs.

- Calorie discount. Foods differ in the proportion of calories we absorb, and in the thermic effect they provoke (energy we burn as we process). Both of these factors serve as calorie “discounts” — we can mentally subtract them from the label.

- Satisfaction (taste, satiety, appetite, cravings). Some foods promote greater fullness and satisfaction (e.g. fiber-rich foods) while others tend to trigger cravings (e.g sugary foods). These aspects are intimately linked to the physiological responses that nutrients elicit, such as our insulin response and hunger hormones.

While there are clear differences between calories, none of them trumps the first principle of weight loss: to lose weight, you need to achieve an energy (calorie) deficit.

Making It Real

What happens when we move beyond tightly controlled, isocaloric human studies, and into the real world? Trials that attempt to mimic the real world teach us several important lessons.

Most Diets Work — At Least In the Short Term

This large 2014 review and meta-analysis of named diets and this 2019 review of low fat versus low carb diets, demonstrate that most diets work — and reinforce the fact that there is no one “best diet”. Presumably, most studies find weight loss because those who enroll in diet studies have committed to changing the way they eat. In other words, simply making weight loss a priority can be helpful.

One Size Does Not Fit All

The average weight loss reported in scientific studies does not tell the full story. Beneath this number, there is often a huge amount of variation in how subjects responded to the same diet. Thus, we shouldn’t expect our results to align with the study average.

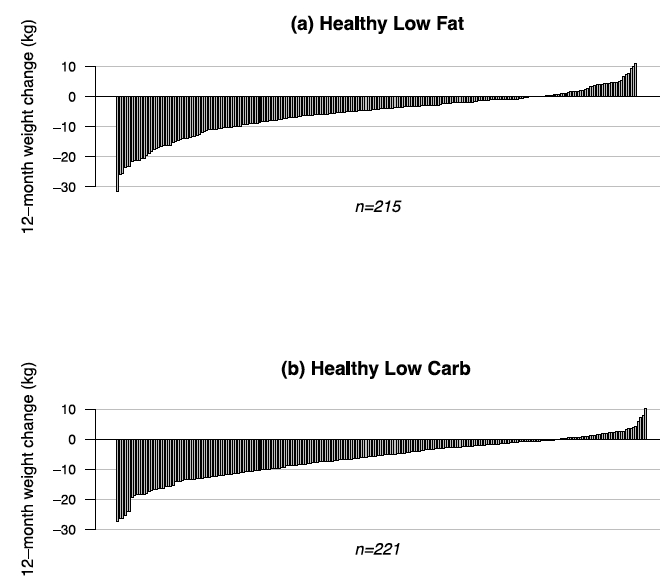

The 2019 DIETFITS study perfectly captures this dramatic variation. One group of obese adults was assigned low fat diet (48% carbs|29% fat|21% protein), while the other was assigned to a low/ moderate carb diet (30% carbs|45% fat|23% protein). Both groups were instructed to (1) maximize vegetable intake; (2) minimize intake of added sugars, refined flours, and trans fats; and (3) focus on whole foods that were minimally processed, nutrient dense, and prepared at home whenever possible. There were no explicit calorie instructions.

Range of weight loss over 12 months from two diets. HLF = (48% carbs / 29% fat / 21% protein). HLC = (30% carbs, 45% fat, 23% protein). Source (Supplement)

On average, those in the low fat group lost about 5.3 kg (11 lbs) while those on the low(ish) carb group averaged 6 kg (13 lbs). Yet, results in both groups ranged from loss of around 30 kg (66 lbs) to gains of 10 kg (22 lbs).

Rather than hunting for “the one true diet”, I prefer to focus on how a diet fits with our preferences, our vulnerabilities, our life, and our biology (though this one is currently impossible to predict!).

Find Your Fit

Here are some factors to consider as you craft your weight loss strategy:

Ease and simplicity. People tend not to stick to diets that are too hard, either mentally or physically (time, effort). This is part of why calorie counting is out of vogue: most people find it too tedious to keep up. Furthermore, it requires many small decisions each day, which is taxing both emotionally and mentally.

Weight Loss Tip: If you love simplicity, consider a diet with an element of fasting (intermittent or time-restricted). This is the ultimate in simplicity, and gives more flexibility in what you eat.

Self Experiment: We can learn a lot from even a single day of (medically appropriate) fasting. Personally, it highlighted my frequent mindless eating, and liberated me from a fear of exploding from hunger. Read my story here.

Tackling temptations and triggers. Many successful diets provide black and white rules that take away the temptations and triggers that sabotage our weight loss efforts. In today’s obesogenic environment, it can be immensely helpful to make a single choice such as “no sugar”, “no carbs” or “no eating after dinner” than to deliberate each potential treat. Such rules often result in reduced calorie intake, and therefore to weight loss.

Weight Loss Tip: Some people can manage treats in moderation, but others struggle not to go overboard. If you struggle with moderation, consider a weight loss strategy that takes your common temptations and triggers off the table.

Feel-Good Factor. A diet that feels awful is not sustainable, even in the short term. The flipside is true of a diet that makes you feel better than ever. Yet, there is a huge amount of variation in how we respond to a given diet. Some people feel deprived on a low-carb diet, while others feel liberated from their cravings. Some people feel energetic and clear-headed on a ketogenic diet, and others feel lethargic and fuzzy-headed.

The Bottom Line

Any diet will promote short-term weight loss as long as it shifts energy balance. Your best bet is a diet that:

- Allows you to achieve a calorie deficit — eat less than your current calorie needs.

- Is simple, and requires minimal effort (mental, emotional, and otherwise).

- Accounts for your personal triggers and temptations.

- Feels good, or at least not tolerable (let’s be realistic…your body may not enjoy a calorie deficit).

- Meets your nutritional needs. Note: Even water fasting can be a viable option in the short term, provided proper medical supervision and supplementation.

The right answer will vary from person to person. It may take you some trial and error to find what works for you. Good luck!

The Long View

The elephant in the room is that most people regain much, or all, of the weight they lose. For lasting weight loss, and lasting health benefits, we need a sustainable diet that fuels our bodies, wards off disease, and helps to fight the uphill battle against weight creep. Stay tuned for more on the science weight maintenance — why it’s so hard and what the victors have in common.

The Twinkie Diet

Just for kicks, here is a Three Step Plan to try the Twinkie Diet. I’d normally advocate a more nutrient dense diet, but this diet could be fun to try for a short experiment. Let me know if you do!

- Calculate how many calories you need in a day (learn how here). Twinkie Diet founder Dr. Mark Haub normally needs about 2600 calories.

- Multiply your calorie needs by 0.7 to get your daily calorie budget at a 30% deficit. For Dr. Haub, this was 1800 calories.

- Divide your calorie budget by 150 (approximate calories per Twinkie) to get your daily Twinkie quota. Dr. Haub can eat 12 Twinkies per day.

For eight weeks, eat only: (1) your daily allowance of Twinkies (or similar calorie treats); (2) a low-calorie protein shake; (3) a serving or two of veggies (fiber!); (4) a multivitamin. That’s it.

Disclaimer: Those with medical conditions should consult their doctor before making significant dietary changes. The Twinkie diet is NOT recommended for long term use. Results will vary. Those who are more overweight will tend to lose more weight than those who are not.