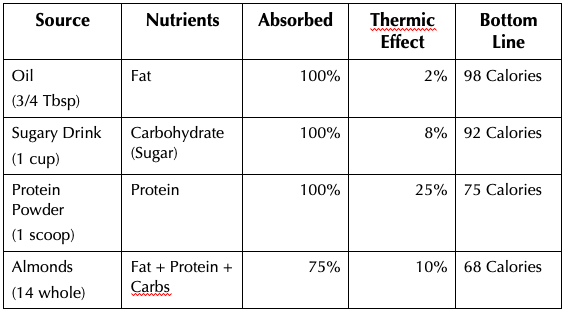

What do a handful of almonds, a spoonful of olive oil, a scoop of protein powder, and a cup of soda have in common? Their labels all read: 100 calories. What does this number really tell us… and what does it not?

The nutrition label on your food only scratches the surface. Even for something as seemingly simple as calorie content, there is much more than meets the eye. Your “bottom line” calorie count — the energy that hits your“calories in versus calories out” balance sheet — may be very different from the number on the label.

Understanding this variation can help support your goals, whether that means stretching a tight calorie budget (hello, fasting days!) or making the most of every calorie when feeding your insatiable teenager.

What determines the “bottom line” calorie content?

The two main factors at play are calories absorbed and calories burned (due to the food). These factors, in turn, are shaped by the nutrient content of your food, the way it’s processed, and your unique physiology.

Before we dive into understanding these factors, and how to use them to your advantage, let’s clarify what calories are, and what they are not.

Calories 101

Calories are not something inherently evil, to avoid. A calorie is a unit of energy that tells us how much potential energy is stored in the food. Food scientists typically measure the energy content of food by burning it in a calorimeter.

Calorie Quickie: A food calorie is the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of one liter of water by one degree.

One capital C food Calorie = 1 Kcal or 1 kilocalorie = 1000 calories (small c) = 4.184 kilojoules

Using calorimetery, fats emerge as the most energetically dense, at nine Calories per gram. Alcohol is next at 7 Calories per gram. Proteins and carbohydrates both provide roughly 4 Calories of energy per gram.

Got Fiber? Carbohydrates in the form if dietary fiber do not contribute to calorie counts on food labels because we can’t digest them. Only the microbes in our guts can break down the bonds and use them for fuel.

The first layer of calorie complexity comes from the fact that we often don’t absorb all of the nutrients in our food.

Calories Absorbed

The energy we can actually absorb from our food is known as the “metabolizable energy”. Yet, food labels typically report potential energy, not metabolizable energy.

How are calories calculated? Food labels are based on The Atwater system. This system uses a formula to add together the calorie contributions of fats, proteins, and carbs. There may be a minor adjustment for imperfect digestibility.

Which Foods Have Absorption Gaps — or Calorie “Discounts”?

When foods require a lot of work to access, digest, and extract the nutrients, there can be substantial gap between calorie label and reality. Nuts are a great example of food that plays hard to get. In order to access the goodness inside, your body needs to penetrate some very tough cell walls. The gap between label and “bottom line” can be up to 25% for whole almonds.

Towards more accurate labels. Scientists determine the true (metabolizable) calories in a food through human studies in which unused is measured in urine and feces. Recently, the USDA has gone nuts testing nuts for their real (metabolizable) values, and have their sights on lentils and chickpeas next. This allows manufacturers to update their food labels with the lower calorie numbers, something that KIND bar makers jumped at.

On the other hand, foods that serve up their nutrients on silver platter offer little to no absorption “discount”. What you see is what you get. Smooth liquids, such as sugar-sweetened beverages, juices, honey, or alcohol are examples of silver platter foods.

In addition to which foods you choose, the way that they are processed (or not) matters greatly as well.

Food Processing: The plot thickens

While the word “processed food” comes with a lot of ugly baggage, this reputation is not entirely deserved. Some types of food processing can be beneficial, depending on your perspective.

Broadly speaking, any food is processed if it has been altered from its original state, whether through mechanical processes (such as grinding or blending), thermal processes (cooking), or both — see the four official NOVA categories here. Such food processing can increase the bioavailability of the nutrients in your food, and bring the percent of metabolizable calories closer to 100%.

In a food scarce environment, this is a great thing. Indeed, development of food processing methods like a mortar and pestle, and cooking with fire, are thought to have provided substantial evolutionary advantages to ancestral humans. In an environment where calories are abundant, and we are constantly tempted to overconsume, this “win” is not necessarily desirable.

When you’re slurping a smoothie, dipping into a jar of nut butter, baking with flour, or downing a protein drink, you are squeezing more calories out of your food than you would from the whole foods versions.

Nut butters. When I want to fill my kids up, I reach for the nut butter! The USDA found that the 25% calorie “discount” from whole almonds disappears when you make the goodness within nuts readily available in almond butter. A small study of peanuts versus peanut butter showed differences of 13–60% in how much fat was “left behind” (lost in feces).

How does food processing impact the bottom line?

On the mechanical front, imagine the cells in your food as little pinatas, containing lots of goodies (nutrients). Food processing can facilitate digestion and absorption by busting open the pinata and increasing surface area (smaller particle size).

The impact of cooking on nutrient availability is complex. Obvious changes in texture, such as the mushy transformation that carrots undergo when you boil them like crazy, are just part of the story. Heat can also alter the digestibility of each macronutrient, such as by causing proteins to unfold (denature) and starches to gelatinize.

A second layer of calorie complexity comes from the fact that we “burn” some of the calories in our meal as we digest, absorb and metabolize the food, and generate heat. This process is known as the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) or Diet Induced Thermogenesis (DIT).

Calories Burned: Thermic Effect of Food (TEF)

On average, we burn through about 10% of the calories in any given meal due to TEF. In other words, it takes roughly 10 calories to tap into the energy available in 100 calories, leaving a net balance of 90 calories on our calorie balance sheet.

Frozen in Time? Feel cold when you fast? It’s not just in your head. It’s well documented that body temperature drops with substantial calorie reduction. It may not feel good, but could pay off…some theorize that lower body temp can help slow down aging. Lack of TEF is one of several factors at play.

The precise TEF (calorie discount) of a meal can vary substantially depending on nutrient composition, size of the meal, and more.

Nutrient content

In general, the effect of TEF tends to be smallest with fats, greatest with proteins, and intermediate for carbs. Commonly cited figures are: 0–3% for fat, 5–10% for carbohydrates and 20–30% for proteins, based on a 1996 review. While the overall nutrient ranking makes sense biologically, the exact numbers should be taken with a large serving of salt because reliable human data are extremely scarce, and hint at a lot of real-world variation.

Got Protein? Boosting the protein content of your meal can help you burn more calories through TEF, though the return on investment is questionable. One study found only a 5% greater TEF in those consuming a 10% protein diet compared to a 30% protein diet.

Digestive Work

Food processing, including mechanical methods (blending, pulverizing) and cooking impact the amount of energy it takes to access the nutrients in your food, including chewing and digestive “work”. In this way, food processing and preparation can doubly impact the calorie “bottom line” of your food.

Meal Frequency

You may have heard that eating more frequent, smaller meals, helps to “boost your metabolism”. This advice is not well supported. In fact, the opposite may be true.

One Meal a Day? A 2016 meta analysis on meal timing, reported that many (but not all) studies found a greater thermic effect (more calories burned) when subjects consumed a single large meal compared to several small meals.

You

Calorie burn through TEF can vary greatly from person to person in ways that we don’t fully understand.

Got TEF? Some studies suggest that calorie burn through TEF may be lower in older adults relative to younger adults. TEF rates may also differ between lean and obese adults, though a causal contribution to obesity is debated.

Putting It All Together In the Real World

These four examples — a sugary drink, a scoop of protein powder, a spoonful of oil, and a handful of almonds — demonstrate how these factors play out.

The oil sits on one extreme. The fats it contains are readily accessible, and require little work to make use of. Thus, we expect almost all 100 calories to hit our “bottom line”. Whole almonds sit on the other extreme. Only roughly 68 of 100 calories consumed will hit your bottom line because of the work required to access and convert the nutrients into fuel.

Note: These figures are very rough estimates. True calories absorbed and burned are impossible to predict, and can vary substantially from person to person. Protein powders bring an additional layer of complexity due to their amino acid composition — this example is assumed to be “complete” such as soy or whey.

Bottom Line

There can be a surprisingly large gap between the number on the calorie label and the bottom line that hits your body. This potential gap is just one of the many layers of complexity behind the notoriously squishy weight management formula: “calories in versus calories out”.

Two people who both nominally consume 2,000 calories per day can have vastly different “net” calorie inputs. Someone who eats a higher fat diet of mostly processed foods is likely hitting their balance sheet with close to 2,000 calories. On the other hand, someone who eats mostly whole, raw plant-based foods might only be logging 1,500 calories. This simple calorie difference may play a role in the complex, and poorly understood link between ultra-processed foods and weight gain.

While I firmly believe that nailing calorie balance is central to weight loss, and to the fight against obesity, this does not mean that calories are all equal. For long term health, and satisfaction, calorie count is just a small part of the story. Whether or not you want to tweak your diet to maximize (or minimize) the calorie gap, you now have the power to make an informed choice!